ilayda

altuntas

Kiara Imblum

This project includes three soundscape activities: creating sound maps, maintaining sound journals, and producing soundscapes, along with visualizations of the resulting soundscapes.

Soundwalk I: Child-centered learning/places

Sound Journal

I chose Costco as my focus for this activity. Although not a typical child-centered space, its varied soundscape can produce a lot of creative learning and creativity for a child in its space. I chose this auditory landscape due to the unique sounds and experiences I've had as a child at Costco. I thought it would be fun to delve into the sound landscape and see how the surroundings may have helped me be imaginative and creative.

Within Costco, I sat in the food court, ordering a pizza and a drink. There were plenty of sounds within this area. The sounds of the soda fountain pouring out drinks, the beepings from nearby registers, clanking carts whizzing by, lots of chatter and different tones of voices, and the tapping of shoes on concrete as people rush to the exit. I did walk around Costco to get familiar with other sounds to see if they blended with the ones near my chosen spot. Throughout Costco, you can hear the humming of fridges trying to stay cool and the different sounds of materials rubbing against each other (styrofoam, cardboard, plastic) as employees stock and customers load items into their carts. These sounds can be heard from the food court due to the open layout and the high ceilings, making the sounds bounce and blend throughout the warehouse.

These sounds, although loud or subtle, can produce a wide amount of curiosity, imagination, and exploration. These sounds mimic other sounds in a child's environment, such as the metal clinking being similar to those on a playground or tons of footsteps similar to walking with their class at school. Although similar, some sounds are new and unique to the Costco warehouse, such as the hum of the mechanics keeping the fridges on or the beeping noises and the smooth sound of rubber rolling on the concrete. Sounds like these naturally engage children’s senses, forcing their creativity to fire up and drive children to explore and engage with them.

I recorded sounds that I heard near the food court, as well as some that I heard throughout Costco. These sounds were constant on the busy Sunday evening I chose to go. It was fun to envision myself as a child exploring Costco; some of these sounds lit my imagination up to think of different scenarios or relate them to different objects I would have imagined if I were a kid entering Costco.

Coscto's auditory landscape could connect to many theoretical frameworks and theories. The landscape encourages child-centered learning, similar to being in an art room. The different sounds naturally provoke children to be curious and explore their surroundings independently. Sensory learning is also happening at the same time. Where children are naturally using their five senses to learn from their environment and practice creativity. Children could also produce their own sounds to then create a sound input to learn more about objects, like tipping over a box of noodles, smacking the watermelons, or picking up boxes and throwing them in the cart. These sounds they produce can make their learning go so much further. These concepts and frameworks are similar to how you would see them in an art classroom. Children are naturally self-driven. In a child-centered approach in the art classroom, children will naturally go toward objects, much like they naturally go toward sounds in Costco. The energy and auditory lighting that Costco provides naturally provide students with opportunities to be creative and learn from the environment, much like being in school.

Sound Map

Soundscape Visualization I: Printmaking

Soundscape I

San Diego Zoo. Animals not only symbolize the progression of history, but their evolutionary processes also reflect changes in human society. The sounds and behaviors of animals are not only manifestations of natural history but can also be seen as part of cultural memory and social cognition. These sounds convey information about biological evolution while also embodying traces of human-nature interaction throughout history. In this way, sound becomes an important medium for understanding history and culture, allowing the symbiotic relationship between animals and human society to be reinterpreted.

The sound elements in the soundscape include:

Hummingbird chirping - This recording was captured at the San Diego Zoo, symbolizing exploration of the place while conveying a sense of remoteness. The hummingbird's chirping evokes the vitality and freedom of nature.

Children’s laughter - This sound element originates from the design of a child-centered educational setting, forming a contrast with the hummingbird's chirping. The laughter not only embodies liveliness and innocence but also emphasizes the educational aspect of the space, creating an atmosphere full of life.

Classical music - I selected classical music as the background sound to add a soothing and harmonious touch to the soundscape. This music balances other sound elements, creating a sense of overall equilibrium and immersion.

City sounds - Two segments of urban ambient noise are contrasted with natural sounds, highlighting the clash and blend of natural sounds with mechanical noises. This contrast not only showcases the interaction between the city and nature but also reflects the tension between humanity and nature in modern life.

Sound of flipping pages - This sound symbolizes the learning function of the space, conveying the meaning of knowledge transmission and cultural accumulation.

Sound of a paintbrush on paper - I also incorporated the sound of a paintbrush moving across paper, emphasizing the importance of artistic creation in this space, representing the process of art and thought.

Soundwalk II:

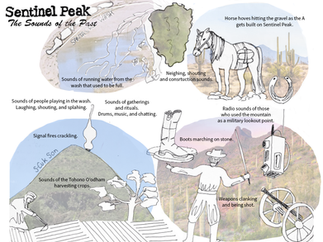

Sounds of the Past (Historical Places)

Sound Journal

The first time I ever visited 'A' mountain was my junior year of college in 2018. Before visiting, I had no idea that the mountain itself is a recognized park. I only visited briefly then, driving around the path and back down the mountain, but it spurred thoughts in my head back then: What makes this mountain so special?

Sentinel Peak, otherwise known as ‘A’ mountain, has been apart of Tucson’s history for a very long time. This mountain has had many names. Its Spanish residents during the 17th century called it “Picacho Del Centinela', and the soldiers called it “Sentinel or Picket Pistols Butte” (Pima County Public Library, 2024). It was also called “Warner’s Mountain” due to Warners Mill being at the bottom. One tribe that resided at the bottom of the peak was called “Chuk-Shon,” translated to “at the foot of the black mountain,” (City of Tucson, 2024) which is where Tucson's original name came from. This mountain had a lot of uses, one main reason being for safety. The O’Odham used it as a way to farm and as a lookout point against those trying to raid them. Soldiers used it as a vantage point, to stay aware of incoming threats.

The letter 'A' didn’t appear on the mountain until 1915. After a big win during a football game against Pomona College, students from the U of a wanted to put a big A on the mountain in celebratory fashion. They used horses to lug up rocks to then make what we know as the giant 'A' on Sentinel Peak today.

Experience:

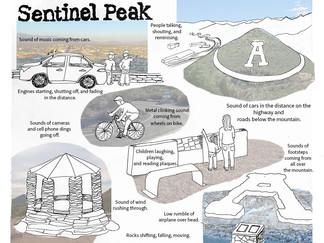

During my drive to the top, I rolled my windows down to enjoy how crisp the air was. The peak feels cooler than it does on ground level. I parked on the edge of the mountain, as everyone else does too, and sat on the edge of the rock wall. I noticed the cars and people in front of me blasting music and talking about life.

As I began recording, I walked along the small road, close to the parked cars, to let others pass. There were about 20 to 30 cars and one biker that passed during my hour-long visit at Sundown. They each interacted with the soundscape, the sound of rubber tires rolling through at various paces against the road. I could also hear the low roaring of airplanes passing over head, adding to the soundscape.

I walked past two cars blasting music. One group was playing rap music and the other playing country at opposite ends. People come up here to the mountain to reflect and enjoy a sensor view. Those men playing this music were all sitting on the rock wall talking, looking out at the city setting.

The more I sat, the more people came and went. A family came and parked nearby where I sat. The children got out excitedly and ran over to the plaque underneath the giant painted A. I think it was their first time here. You could hear the shuttering of a camera as they took photos of both the scenic Tucson landscape and of themselves. They didn’t spend too much time up at the top. Along with the sounds of families enjoying their time spent here, there is a low roar coming from the cars passing from beneath me. In the distance you can see and hear the highway, and below there are local streets that cars passed by on.

During my visit, I walked some of the paths, my shoes kicking up the rocks, changing the grounds beneath me. These paths were interconnected, some leading to the top of the giant A, some leading around the mountain, and some leading to nowhere in particular. I had no idea these paths existed on top of the A. There were plaques where people could read about Sentinel Peak history, which I watched many children run up to and read.

All in all, this space is used as a community gathering spot, gathering those who have never been here and want to feel apart of the history and those who have been. Although the space has a lot of history, you wouldn’t hear the narratives of the past as those in the presence are making new memories.

Reflection:

Engaging with Sentinel Peaks sounds shaped my understanding of what it is now: a place for people in the community to gather, reflect, discover, and spend time together. These every-day sounds—cars driving, bikes, conversations, music—are a symphony of history and community. These sounds intersect with the proposed sounds of the past, such as the o’odham settlers discussing their own lives or the soldiers discussing orders of the day.

In creating this sound map, I engaged with the theme of community memory and social participation. The sounds I recorded reflect the vibrant lives of those that live in and visit Tucson. The sounds I found from the past are to intertwine the historical sounds to serve as a reminder of the history behind the mountain. Together they encourage listeners to reflect, emphasizing just how important it is to acknowledge the history that shaped our town into what we know today.

Engaging with the Sentinel Peaks sounds shaped my understandings of its social and historical attributes. I became aware of how our present-day sounds filled this auditory landscape, muffling those of the past. The atmosphere being filled with modern-day cars, bikes, cellphone clicks, and music overshadows what this place once was. This was part of the challenge in making this sound map. This struggle shows the tension between urban development and preservation of historical narratives. However, the space itself is a true testament to the resilience of the past.

This project can be a way to elicit memories. If this was used as a tool for the community, people could contribute their own sounds or memories to it. This could help us deepen and enrich the history of Sentinel Peak with community narratives and actions as a form of empowerment for those who may not have had their story told. The sounds recorded and recreated, along with the stories told, are a way to build connection and reflect on the past, bringing in the community to connect our shared identity.

References:

A mountain, or Sentinel Peak. Pima County Public Library. (n.d.). https://www.library.pima.gov/content/a-mountain-aka-sentinel-peak/

Sentinel Peak Park. City of Tucson. (n.d.). https://www.tucsonaz.gov/Departments/Parks-and-Recreation/Parks/Sentinel-Peak-Park

Tucson Arizona. LocalWiki. (n.d.). https://localwiki.org/tucson/Sentinel_Peak%3A_%22A%22_Mountain

Sound Map

Soundscape Visualization II: Digital Collage

Soundscape II

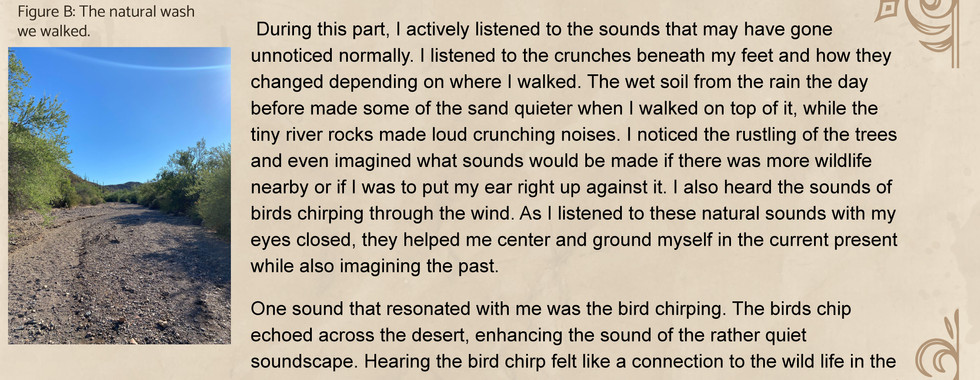

Soundwalk III: Decolonial Practices

Sound Journal & Map

Soundscape Visualization III: Sound Sculptures

Soundscape III

text.

Power in Numbers

30

Programs

50

Locations

200

Volunteers