ilayda

altuntas

Robyn Ann Stea

This project includes three soundscape activities: creating sound maps, maintaining sound journals, and producing soundscapes, along with visualizations of the resulting soundscapes.

Soundwalk I:

Child-centered learning/places

Sound Journal

The space I chose for my sound map was a local park. I chose a specific park where families often bring their children to explore the playground, swing on the swing set, and check out the small community library. Since I visited during the day (usually families come around dusk) the soundscape was different than what I expected. Instead of the usual laughter and playful shouting, I mostly heard birds chirping, cars in the distance, and the occasional voice calling for a dog. There was also occasional low conversation in the background from the few people who were there.

Even without children present, I could see how this environment has the potential to nurture creativity. The sounds of birds, trees and wind connect to what Sobel (2004) describes as the happiness and freedom children experience in nature. The open environment allows them to be creative with inventing stories, games, and imaginative play. The park itself can become part of the creative process.

Lowenfeld (1960) mentions that children’s creative intelligence develops through free exploration, where their individuality and problem-solving skills emerge. A park offers an open-ended space: children are free to use the sounds, textures, and movements around them as material for imagination. The environment invites them to engage on their own terms rather than prescribed activities.

Marshall (2014) adds another dimension by suggesting that art and creativity are forms of research. If we frame a child’s play in the park as inquiry, the sounds - swing set, birds, and voices - become prompts for investigation. The park becomes a place for for developing curiosity and new knowledge.

Overall, the sound map exercise reminded me that learning and creativity are deeply tied to place. Even seemingly ordinary spaces can foster imagination and curiosity.

Sound Map

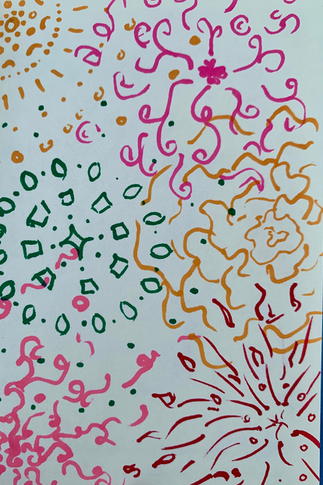

Soundscape Visualization I: Printmaking

I used carved images of birds and trees to express the recorded sounds of birdsong and the natural environment I created. The birdsong is crisp as if whispering nature’s stories, full of life and vitality. The sound of the trees conveyed through the rustling of leaves in the wind and the gentle sway of branches, brings a rhythm of tranquility and harmony. These sounds intertwine to create a vivid natural scene, a layered, lively nature soundscape. Through this symbolic artistic expression, I echo the layers of sound in the recordings and attempt to visualize this auditory atmosphere, creating a space suitable for children’s learning and drawing. In this environment, children can engage with the singing of birds, the murmurs of trees, and other natural sounds, gaining inspiration and experiencing the immersive calm that the flow of sound brings to the space.

Soundscape I

I titled my soundscape “A Day at the Park in September” because I wanted to capture the essence of a child-centered place where learning, play, and imagination unfold naturally. Parks have the potential to serve as informal classrooms, offering the opportunity to explore, listen, move, and develop a sense of belonging. This idea aligns with place-based education, which emphasizes learning through direct engagement with local surroundings and the communities that shape them. My soundscape is composed of layered recordings including a creaky swing set, children playing from a nearby school, birds singing, and an acoustic cover of a song from the Disney movie Beauty and the Beast. These elements work together to evoke the everyday sensory experiences that help children form relationships with their environment. The swing’s creak becomes a rhythmic marker of play; the voices of children playing highlight communal learning and shared space; the birds singing points to a park as a natural, outdoor environment; and the gentle melody introduces familiarity, comfort, and cultural memory. By weaving these sounds together, the piece reflects how children make meaning through place and how ordinary environments can become sites of curiosity, emotional connection, and embodied learning.

Soundwalk II: Sounds of the Past

(Historical Places)

Sound Journal

For this project, I chose to explore El Tiradito, also known as the Wishing Shrine or the Shrine of the Unforgiven. Located on South Main Avenue in Tucson’s historic Barrio Viejo, El Tiradito has stood as a symbol of love, loss, and cultural resilience since the late 1800s. Legend tells of a man who was killed for his forbidden love affair. Because his death was tied to a “sin,” the Catholic Church denied him burial in consecrated ground. Instead, his loved ones marked the site of his death with candles and prayers, giving rise to El Tiradito, meaning “the little castaway.” Though the original shrine was destroyed during urban redevelopment in the early 1900s, it was rebuilt around 1940 and has endured as a symbol of love, loss, and redemption for the Tucson community.

Soundwalking through El Tiradito allowed me to experience its history not just visually, but through layers of sound that revealed its living spirit. The neighborhood’s ambient noise—the hum of nearby traffic, snippets of conversation, birds singing, wind, and the faint rustle of someone adjusting a piece of memorabilia—merged into an audible collage representing the sacred space. The shrine is adorned with candles, flowers, religious icons, photographs, and handwritten notes rolled tightly into the cracks of its brick walls. According to local legend, if you light a candle and it burns through the night, the wish tucked into the wall will come true. Listening to this space, I realized that El Tiradito is both a physical and sonic memorial—one that carries sounds of hopes, prayers, and memories.

This site also plays a vital role in Tucson’s annual Día de los Muertos celebrations, when visitors bring offerings, music, and art to honor their ancestors. During this time, the shrine becomes a focal point of collective remembrance and cultural pride.

My sound collage integrates my field recordings with clips of locals describing the shrine and traditional Día de los Muertos music. It concludes with the tolling of bells—symbols of remembrance, loss, and spiritual endurance. As a form of socially engaged art, the piece invites reflection on how sound preserves culture and amplifies community resilience. Expanding this project could involve inviting others to contribute their own recordings or oral histories, transforming the sound map into a living archive that celebrates Tucson’s collective memory and reaffirms belonging through shared listening.

Sound Map

Soundscape Visualization II: Digital Collage

When I first started this collage, my idea was simply to show Old Main as a recognizable landmark on campus. But as I explored different materials and textures, the piece gradually shifted into something more atmospheric. I began bringing in desert plants, bold colors, and layered shapes that reminded me of the sensations I usually feel around Old Main: bright sunlight, the sharp lines of cactus, and the movement of wind. The sound recordings I took on campus also influenced the composition's development. The rhythm of footsteps and the soft shifting of leaves encouraged me to add wave-like patterns and distortions, making the image feel more alive than the original plan.

One of the biggest challenges was keeping all the elements balanced. There were moments when the collage felt too crowded, and Old Main started to disappear behind everything else. I spent time adjusting the scale and contrast so the building could remain the main focus while the surrounding layers supported the feeling of place. Translating sound into visual form was also difficult at first, but experimenting with repeated lines and flowing shapes helped me find a connection between what I heard and what I could show. Through this project, I realized that sound and visual art share similar rhythms; they both shape how we experience a space, and combining them allowed me to understand Old Main in a more sensory and emotional way.

Soundscape II

For this project, I chose to explore El Tiradito, also known as the Wishing Shrine or the Shrine of the Unforgiven. Located on South Main Avenue in Tucson’s historic Barrio Viejo, El Tiradito has stood as a symbol of love, loss, and cultural resilience since the late 1800s. Legend tells of a man who was killed for his forbidden love affair. Because his death was tied to a “sin,” the Catholic Church denied him burial in consecrated ground. Instead, his loved ones marked the site of his death with candles and prayers, giving rise to El Tiradito, meaning “the little castaway.” Though the original shrine was destroyed during urban redevelopment in the early 1900s, it was rebuilt around 1940 and has endured as a symbol of love, loss, and redemption for the Tucson community.

Soundwalking through El Tiradito allowed me to experience its history not just visually, but through layers of sound that revealed its living spirit. The neighborhood’s ambient noise merged into an audible collage representing the sacred space, which also has inspired my visual collage. The shrine is adorned with candles, flowers, religious icons, photographs, and handwritten notes rolled tightly into the cracks of its brick walls. According to local legend, if you light a candle and it burns through the night, the wish tucked into the wall will come true. Listening to this space, I realized that El Tiradito is both a physical and sonic memorial—one that carries sounds of hopes, prayers, and memories.

Soundwalk III: Decolonial Practices

Sound Journal

"Tracing the Footsteps"

The first soundwalking prompt was an invitation for me to drop into my own body’s sensations and notice its response the desert. As I quieted my own inner voice, I was able to pick up subtleties that I wouldn’t have heard otherwise. I heard the crunch of my own boots against the sand. Gentle wind weaving its way between tree branches. I noticed a birds nest, delicately perched on a hidden branch. A wave of gratitude swept over me as I walked in the shade of the vegetation, away from the intensity of the bright sun. I thought of the desert’s history and of people who have come before, mindful that they probably walked the same path as I did.

"Listening and Touch"

As the second soundwalk invited me to interact physically with the desert, I found myself picking up various sticks, rocks, and leaves, rubbing them between my fingers and feeling their various textures. I payed close attention to how they interacted with each other; some sounds were manufactured by my manipulation of the materials, and other sounds were simply a byproduct of me occupying space. I began to tap various objects with a broken stick, observing the audible textures and effects.

"Embodying Decolonization"

This soundwalk began as a walk, and then quickly transitioned into a “sound-sit”; I plopped myself onto a patch of sand under a tree and began to observe. I was invited at various times to engage my body, such as lifting my arms or swaying. I noticed the feel of the earth beneath my body; I felt small stones embed themselves into the backs of my legs as I sat. I began to create a mandala using medium-sized rocks and various found materials. I felt my body relax as I worked, feeling at peace with the land. In this moment I felt less of a steward and more a collaborator - I chose to engage from a place of humility, asking the desert what it wanted me to learn, rather than assuming a position of false power.

In summary, this soundwalk opened my eyes to my own relationship with the earth - it allowed me to slow down, breathe deeply, and forget about my busy week ahead. I was sad to leave - I felt as though our class had been led to our own oasis, away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life. I left with a newfound sense of gratitude from the experience.

Sound Map

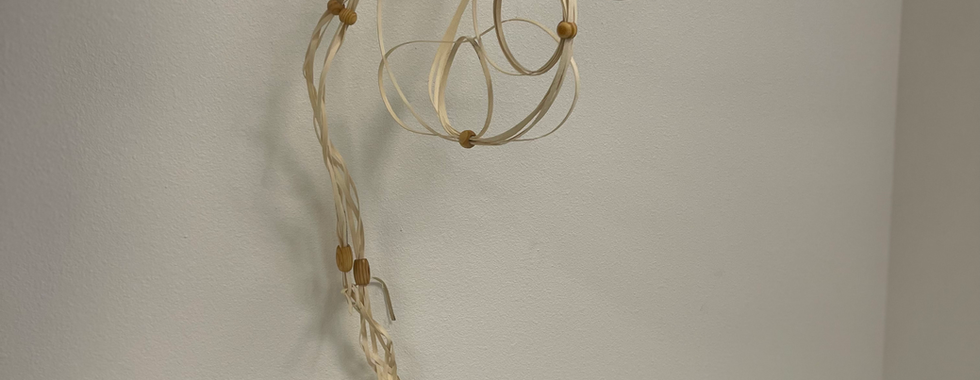

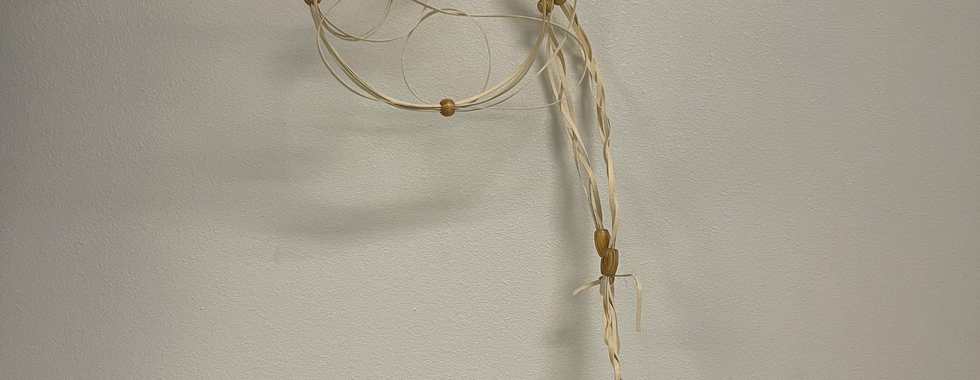

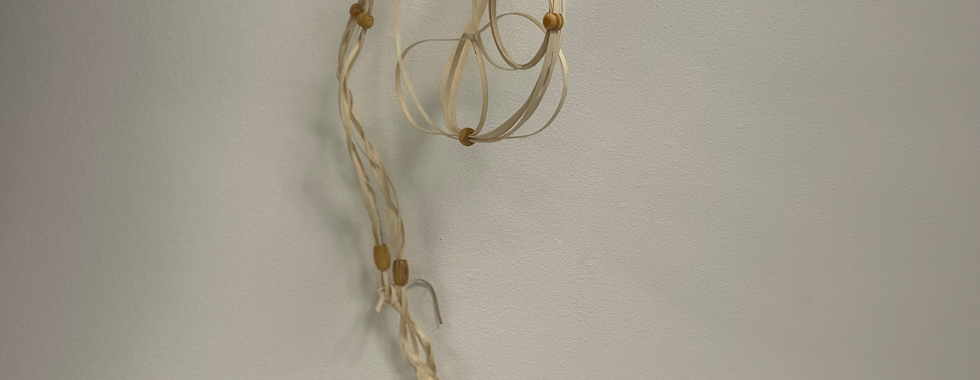

Soundscape Visualization III: Sound Sculptures

Soundscape III

Designing a soundscape rooted in decolonizing principles required me to think beyond aesthetics and consider how sound can reorient our perspective of land. In this project, I created an immersive sound environment using found recordings of coyotes, wind, birds, and minimal ambient music layered beneath natural elements and my own personal recordings of the desert. My goal was not to romanticize the desert as an empty, untouched wilderness, but instead to frame it as a living and culturally situated place.

The soundscape serves as an entry point for critical, place-based art education. When listeners engage with these layered sonic textures, they have the opportunity to experience the desert as a multisensory ecosystem. This can prompt questions about whose stories are emphasized when we imagine a place and whose are ignored. By emphasizing natural sound, the piece encourages participants to attune their own bodies, memories, and interpretations to the space. In this way, the soundscape becomes both a listening practice and an embodied pedagogy.

At the same time, the ambient music woven throughout the composition acts as a connective thread holding the various sounds together. Its minimalism mirrors the stillness of the desert while subtly reminding listeners that interpretation is a collaborative act between artist and environment.

Ultimately, this soundscape aims to nurture a deeper understanding of place through listening. By inviting participants to immerse themselves in the dynamic sounds of the desert, the piece presents the land as vibrant, interdependent, and worthy of care.

Power in Numbers

Programs

Locations

Volunteers