ilayda

altuntas

Mandi Smith

This project includes three soundscape activities: creating sound maps, maintaining sound journals, and producing soundscapes, along with visualizations of the resulting soundscapes.

Soundwalk I: Child-centered learning/places

Sound Journal

Were it not for art education, the child would scarcely be reminded of the meaning and quality of (his/her/their) sense organs. Yet their proper use is of such vital importance, for the enjoyment of life and for vocational purposes, that we cannot afford such neglect. In creative activity perceptual growth can be seen in the child's increasing awareness and use of kinesthetic experiences, from the simple uncontrolled body movements during scribbling to the most complex coordination of arm and linear movements in artistic production. It can be seen in the growing response to visual stimuli, from a mere conceptual response as seen in early child art to the most intricate analysis of visual observation as seen in impressionistic art in which form, color, and space are subordinated to the impression of the total picture” (Lowenfeld & Brittain, 1964).

I've been increasingly interacting with learning through my own sensory experiences. Reflecting in this way has taught me a lot about how bodies react and interact with space and sound. I would like to focus on a child-centered site for my next soundwalk, placing myself into a memory and novelty at the same time, recalling my own experiences in spaces where I feel free to explore and imagine. Recently, my family and I brought my niece to a water park for her birthday. She, being on the spectrum, approached the water trepidatiously, while most children her age exhilarated and unaware of her nervousness, sped by her to go up to the slides again after just completing the last round. I watched her from the sunchairs as she looked around curiously and decided to accompany her. Perhaps, in this moment, there was something I could learn from too.

In my attempt to understand this adjacency for me, a child learning site, and Viktor Lowenfeld and Lambert Brittan’s classroom-based theories in the book Creative and Mental Growth, I learned that these ideas might aid educators in balancing the growing components of children's development. A child's development encompasses emotional, intellectual, physical, and social growth and each of these experiences interacts through creative expression.

In regard to my niece, her attention was caught by the sometimes overwhelming noises coming from the rhythmic pouring of buckets overhead, the rush of slides, and the sloshing of water between her toes and beneath her feet. For thirty minutes, we lingered at the shallow edges, splashing quietly, watching the energetic movements of other children. In this moment, I realized that creativity and learning can emerge not just in active play but also in stillness, silliness, splashing water with our feet, and observation of watching where the sprinkles of water landed. Together we explored the space, becoming aware of how we wanted to interact with the objects around us.

As we have discussed in class in prior weeks, the environment itself became an active participant in education, and I noticed that for her the splashpad was like a study subject of sensory and social experience. I observed my niece negotiating excitement and overstimulation, calming herself down and gradually finding comfort in the rhythms of water and movement where she stood.

Lowenfeld and Brittain (1964) remind us that a child’s creative growth is deeply tied to process and experience, not the final product. The sounds of buckets tipping, water sloshing, and distant laughter all became part of this emerging scaffold for engagement, imagination, and self-expression.

As I prepare my soundwalk, I ask myself if these sounds guide my reflections on play-based learning and creative inquiry. Could listening deeply to the aquatic environments reveal ways children interpret, adapt, and engage with space on their own terms? In imagining these sounds as my guide, I realize that sound can become a bridge between observation and understanding. In my niece's case my observations led me to understand she needed to engage with the activity in her own timing and way. I was learning this too as we gradually went from splashing with our feet to splashing with our hands. When she needed time we took time and we learned how to navigate that sensory experience together. Leaning into her cues helped me comprehend the potential of this type of child-centered art education and taught me how to reflect while still teaching in a way that respects my niece's pace.

References

Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1964). Creative and mental growth (4th ed.). Macmillan.

Zimmerman, E. (1980). Approaches to art in education. Studies in Art Education, 21(2), 70–71.

Sound Map

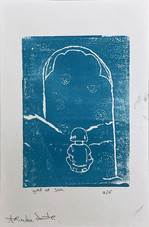

Soundscape Visualization I: Printmaking

I used carved images of birds and trees to express the recorded sounds of birdsong and the natural environment I created. The birdsong is crisp as if whispering nature’s stories, full of life and vitality. The sound of the trees conveyed through the rustling of leaves in the wind and the gentle sway of branches, brings a rhythm of tranquility and harmony. These sounds intertwine to create a vivid natural scene, a layered, lively nature soundscape. Through this symbolic artistic expression, I echo the layers of sound in the recordings and attempt to visualize this auditory atmosphere, creating a space suitable for children’s learning and drawing. In this environment, children can engage with the singing of birds, the murmurs of trees, and other natural sounds, gaining inspiration and experiencing the immersive calm that the flow of sound brings to the space.

Soundwalk II:

Sounds of the Past (Historical Places)

Sound Journal

In exploring histories that resonate, I chose to create a soundscape that captures the layered memories surrounding Biosphere 2 as a site of local significance for the Arizona community and as a global symbol of environmental innovation. The sounds in my composition were recorded during a visit and tour with my family of this rather remarkable experimental space in Oracle, Arizona, allowing me to have such a unique personal experience as I began to understand how my own process of listening and recording could serve as a form of data collection in arts-based research, connecting my personal encounter with the broader ecological and scientific narratives.

The goal of this work is to capture the living acoustics of a scientific space that continues to resonate with history. As I toured the space and went through the sequence of sounds, the experience shifted from natural environments to human-engineered spaces (for example, you will hear generators and machines operating in this environment), reflecting how the Biosphere blends science, technologies, architecture, and ecology into a unique system.

Visiting this place with my family was a truly memorable experience. It was my first time exploring, and walking through its biomes felt like stepping into a living archive of scientific imagination because you're stepping into a really unique environment made to sustain human and biological life and to test the capabilities of our technology which in its original function was developed to recreate earth’s biosphere on other planets.

Soundscape Visualization II: Digital Collage

Originally built in the early 1990s as an experiment in creating a self-sustaining ecological world, Biosphere 2 continues to evolve as a center for education and research under the University of Arizona. It serves as a bridge between art, science, and ecology, helping visitors reflect on our planet’s delicate balance and the interconnected systems that sustain life and I felt this fit the historical soundscape project, as it is such a lush environment for learning about our beautiful biosphere!

Moving from the Rainforest to the Ocean and Desert rooms, I was struck by how each space carried its own rhythm of sound and life. You will notice in the soundscape the sound of other ongoing projects going on within each environment, updating and constantly producing scientific experiments, and it's actually taking shape within its own soundscape in this space and has created a whole new element of life to the biosphere. Projects that are intended to ask questions of climate change look at the overproduction of algae in oceans Dynamic projects that continue to shape our world and make it better with their data collections.

I was fascinated by the plants and how they coexist, even learning about the challenges faced in the early experiments when oxygen levels dropped. Seeing the resilience of these plants, which, from early experiments in the 1990s until our present moment, have had a thriving life overcoming the harshness of those once terrible conditions. I imagine how the site has adapted over time, and it's inspiring me to think about learning as an ongoing, living process and one that continues to grow, much like the Biosphere itself.

Soundscape II

In exploring histories that resonate, I chose to create a soundscape that captures the layered memories surrounding Biosphere 2 as a site of local significance for the Arizona community and as a global symbol of environmental innovation. The sounds in my composition were recorded during a visit and tour with my family of this rather remarkable experimental space in Oracle, Arizona, allowing me to have such a unique personal experience as I began to understand how my own process of listening and recording could serve as a form of data collection in arts-based research, connecting my personal encounter with the broader ecological and scientific narratives.

The goal of this work is to capture the living acoustics of a scientific space that continues to resonate with history. As I toured the space and went through the sequence of sounds, the experience shifted from natural environments to human-engineered spaces (for example, you will hear generators and machines operating in this environment), reflecting how the Biosphere blends science, technologies, architecture, and ecology into a unique system.

Visiting this place with my family was a truly memorable experience. It was my first time exploring, and walking through its biomes felt like stepping into a living archive of scientific imagination because you're stepping into a really unique environment made to sustain human and biological life and to test the capabilities of our technology which in its original function was developed to recreate earth’s biosphere on other planets.

Soundwalk III: Decolonial Practices

Sound Journal

Listening as Learning: Composing with the Desert

“There has been a proliferation of research regarding the social and cultural aspects of how people learn. Learning as a sociocultural process emphasizes the situated, coconstructed, mutually constitutive nature of persons, activity, and environment” (Kimberly A. Powell, 2010, p. 101).

When I first read these words, I didn’t yet know what it meant to learn with the land. But at Saguaro National Park West, I began to understand. The afternoon sun leaned softly against the stone, and the wind whispered in a language older than sound.

As we began our soundwalk, I tried to listen, embodying an experience that was mine but also did not belong to me. I was in awe of the place and wanted to know or imagine the stories it carried before me there.

The desert felt like an instrument that played its own composition, and I found myself listening for where I belonged within it. Meditating and engaging with the materials of the land, I chose to engage the most texturally with the landscape. Beneath my feet, a slow percussion of pebbles marked each step, while the wind hummed softly through the cacti, brushing against my hair as it whispered across the rocky landscape. Over time, that same wind had carved and eroded the peaks around me, shaping them as surely as it was shaping my thoughts. Each sound became a syllable in a sentence the land had been composing for centuries.

Kimberly Powell, Ilayda Altuntas, and Michael Bricker (2024) write that walking is not merely about movement from one point to another but a performative practice of knowledge in the making. As I wandered from the group, finding solace in my own belonging there, I thought of how knowledge sometimes hides in stillness. I pressed my hand into the sand and sifted small pebbles through my fingers; each stone carried its own voice, the smallest particles arising in volumes at a microscopic level, which was absolutely awesome to think about. what could my ears not perceive as much as what could they perceive? With the larger rocks I rubbed two stones together until they sang in high, grainy notes as if to recall the making of arrows or tools. I also arranged the rocks into tiny sculptures, gestures that felt as if something other than my memory were guiding me. I listened to the desert for what the sound told me that day and to the stories held within that landscape beyond my own relativity.

When the wind rose, I lifted my phone toward it, recording the air itself, the rhythm of the brush, and the quiet pulse of my own breath. I was one note among many, carried in the expanse of the desert heat.

I was only sound and some of my body's own resistance to the space, for example, a dry mouth from lack of occasional dehydration, sniffling from minor allergies, and learning to adapt to the environment I was in, while finding my way in that place.

Listening, I realized, is an act of vulnerability. To truly hear is to let the world move through you and learn something from it. The stillness of Saguaro made me aware of how much I depend on the noise of life and how equally rare it is to listen without the need to respond to it. In the hush between gusts of wind, I could almost sense the petroglyphs speaking marks left by hands that, like mine, once tried to make sense of their place in the world through wayfinding.

Powell (2010) reminds us that learning is a conversation between self, activity, and environment. In the desert, that conversation felt alive, almost sacred. Every sound, every movement, every breath seemed to stitch me into the larger fabric of place. And perhaps that is what this soundwalk really taught me, which is to say that knowledge is not always built from analysis or argument, but from attention. From being still long enough to feel the world noticing you back. As I begin to shape this experience into visual form, I want to honor that delicate reciprocity: the desert’s patience, the silence between sounds, and the quiet ways learning finds its voice.

References

Powell, K. A. (2010). Composing sound identity in Taiko drumming. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 41(2), 101–119.

Powell, K., Altuntas, I., & Bricker, M. (2024). Defamiliarizing a walk. Qualitative Inquiry, 30(4), 1–15.

Soundscape Visualization III: Sound Sculptures

Soundscape III

Power in Numbers

Programs

Locations

Volunteers