ilayda

altuntas

Lei Wang

This project includes three soundscape activities: creating sound maps, maintaining sound journals, and producing soundscapes, along with visualizations of the resulting soundscapes.

Soundwalk I: Child-centered learning/places

Sound Journal

I chose the arcade, Round 1, as my sound collection space. I often go there on weekends, especially during summer vacation, and I noticed that families with children usually gather there on Friday and Saturday nights. The atmosphere is always full of energy, with loud and overlapping sounds from games, people, and music. I chose this space because it is a place where children and parents interact freely, and the sounds reflect a unique mix of play, excitement, and social connection.

The moment I walk into the arcade, I was immediately surrounded by layers of sound—machines buzzing, game music looping, coins clinking, and people shouting or laughing. The noise level is high, but it also gives the place a lively rhythm. For example, the game Hungry Hungry Hippos creates a strong beat when children hit the controls, accompanied by their bursts of laughter and shouts as they compete. I also recorded sounds from the air hockey table, where the puck striking the board mixes with children’s playful cheers and parents’ encouragement. These sounds are not isolated; they blend to form a vibrant soundscape that reflects the arcade’s fast-paced, immersive environment.

For children, such sounds open up opportunities for imagination and creativity. The repetitive rhythm of the machines or the unpredictable laughter of peers can inspire them to move, dance, or even invent stories about their play. The soundscape allows children to express their feelings more openly: cheering loudly, imitating the noises of machines, or creating playful conversations with friends. These moments not only give them joy but also strengthen their social skills. Parents’ active participation, such as playing air hockey or cheering alongside their kids, adds another creative dimension, making the play experience a shared family performance. The arcade’s environment becomes a stage where children’s creativity naturally flows from sound, play, and interaction.

These observations connect with ideas in early childhood art education, especially child-centered and play-based learning. Eisner (2002) reminds us that the arts encourage multiple forms of expression beyond language, and in the arcade, children’s laughter, rhythm, and playful sounds become a natural part of their creative process. This also relates to Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory, since children’s creativity is strengthened through interaction, not only with peers but also with parents who join in the games. Finally, the setting reflects Dewey’s (1934) idea of art as experience, where the integration of body, senses, and environment creates meaningful opportunities for expression. Even though the arcade is not a classroom, it works as an informal learning space where sound, play, and relationships nurture children’s imaginative growth.

References

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Minton, Balch & Company.

Eisner, E. W., & Yale University Press, publisher. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind (1st ed.). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300133578

Vygotskiĭ, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society the development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Sound Map

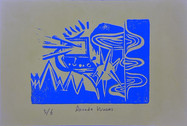

Soundscape Visualization I: Printmaking

I used carved images of birds and trees to express the recorded sounds of birdsong and the natural environment I created. The birdsong is crisp as if whispering nature’s stories, full of life and vitality. The sound of the trees conveyed through the rustling of leaves in the wind and the gentle sway of branches, brings a rhythm of tranquility and harmony. These sounds intertwine to create a vivid natural scene, a layered, lively nature soundscape. Through this symbolic artistic expression, I echo the layers of sound in the recordings and attempt to visualize this auditory atmosphere, creating a space suitable for children’s learning and drawing. In this environment, children can engage with the singing of birds, the murmurs of trees, and other natural sounds, gaining inspiration and experiencing the immersive calm that the flow of sound brings to the space.

Soundscape I

Soundwalk II:

Sounds of the Past (Historical Places)

Sound Journal

For my soundscape II project, I chose Old Main as my historical site. Before I began my studies, I read about the University of Arizona and noticed Old Main as one of the most recommended landmarks. The name stayed with me until the first week of my first semester, when I finally stood before it. Completed in 1891, Old Main is the university’s oldest building and once housed all classrooms and offices. Today, it stands as a historic landmark, a living reminder of the university’s beginnings and a symbol of continuity between past and present.

Soundwalking around Old Main allowed me to experience this history in a multisensory way. The rhythmic crunch of sand beneath my shoes, the chirping of birds, the laughter and footsteps of students passing by, and the soft hum of the fountain together created an invisible timeline connecting generations. These sounds reminded me that history is not silent; it vibrates through daily interactions and environmental rhythms. The faint echo of the bell tower carried a sense of tradition, calling to mind countless ceremonies, beginnings, and farewells that have taken place on this campus.

Listening to history through sound was both inspiring and challenging. It required slowing down, filtering out distractions, and attuning myself to subtle layers of meaning, how sound reflects belonging, movement, and memory. I realized that what seems ordinary, like footsteps or chatter, carries traces of social life and emotional connection to place.

My sound map acts as a form of socially engaged art by weaving together personal observation and collective experience. It highlights how shared soundscapes connect people across time and background. Through this project, I began to see sound not just as documentation but as dialogue, inviting others to listen, reflect, and imagine their own relationship with Old Main.

In the future, this project could expand into community dialogue or educational programs, encouraging students and residents to explore campus history through listening. Sound can foster awareness, complicate dominant narratives, and deepen our collective sense of place, reminding us that every space carries stories waiting to be heard.

Sound Map

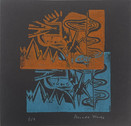

Soundscape Visualization II: Digital Collage

When I first started this collage, my idea was simply to show Old Main as a recognizable landmark on campus. But as I explored different materials and textures, the piece gradually shifted into something more atmospheric. I began bringing in desert plants, bold colors, and layered shapes that reminded me of the sensations I usually feel around Old Main: bright sunlight, the sharp lines of cactus, and the movement of wind. The sound recordings I took on campus also influenced the composition's development. The rhythm of footsteps and the soft shifting of leaves encouraged me to add wave-like patterns and distortions, making the image feel more alive than the original plan.

One of the biggest challenges was keeping all the elements balanced. There were moments when the collage felt too crowded, and Old Main started to disappear behind everything else. I spent time adjusting the scale and contrast so the building could remain the main focus while the surrounding layers supported the feeling of place. Translating sound into visual form was also difficult at first, but experimenting with repeated lines and flowing shapes helped me find a connection between what I heard and what I could show. Through this project, I realized that sound and visual art share similar rhythms; they both shape how we experience a space, and combining them allowed me to understand Old Main in a more sensory and emotional way.

Soundscape II

Soundwalk III: Decolonial Practices

Sound Journal

That was my first time visiting Saguaro National Park West. For me, it felt like an escape from the hustle and bustle of campus life—a quiet and peaceful space surrounded by an ancient landscape. At the same time, I felt a deep sense of awe standing in this historical place. Even though it is a national park, I was surprised by how few visitors were there. The stillness created a mysterious atmosphere that made me curious about the land’s past and its stories that continue to live through the wind, stones, and cacti. I began this sound walk with both excitement and humility, wondering how I could listen differently—to the land, to its history, and to my own inner voice.

Soundwalking I: “Tracing the Footsteps”

During this sound walk, I was most drawn to the sound of my hiking shoes touching the rocky ground. Each step created a dialogue between me and the land—like a quiet conversation with the past. The rocks varied in shape and texture, and when I changed the pressure of my footsteps, the sound also changed in tone and rhythm. I realized that listening to the ground required careful attention; my movement was not just physical but also a gesture of respect. As a visitor, I became aware that this land holds memories of those who walked before me, Indigenous peoples whose presence continues to shape this place.

When I found this heart-shaped stone, I stopped and felt a quiet connection with the land. Its shape reminded me of care and strength, as if the land was speaking in silence. I realized that listening during the walk was more than hearing sounds; it was about feeling the place and respecting its history.

Soundwalking II: “Listening and Touch”

I stopped beside a group of rocks covered with pale green lichen. Their surfaces felt rough and alive, like a quiet record of time. As I touched the cool stone, I could feel the mix of dryness and softness where the lichen spread. The background was filled with the steady sound of wind, the faint buzz of flies, and the soft crunch of sand and small rocks under my shoes. These layers of sound and texture made me slow down and listen more carefully. I realized that active listening is also a form of touch; it helps me sense the land’s presence and respond with awareness and respect.

Soundwalking III: “Embodying Decolonization”

When I reached the area with ancient carvings, I felt quiet and amazed. The lines on the rocks looked simple but full of stories. I touched the warm surface and felt the rough texture under my hand. The sun was strong, and every sound, my steps, the wind, felt heavier here. I realized that walking in this place means moving with care, not as a tourist but as someone learning to listen. Thinking about history and memory, I saw how these carvings are still alive. They remind me that the land remembers. Decolonizing, for me, means slowing down, paying attention, and giving space for those voices to stay seen and heard.

These soundwalking experiences taught me to slow down and listen with care. I learned that the land speaks through sound, texture, and silence. This awareness helps me see listening as a way to connect and respect. In my future art and teaching, I want to keep this mindful approach, creating spaces where learning grows from being present with the land and its stories.

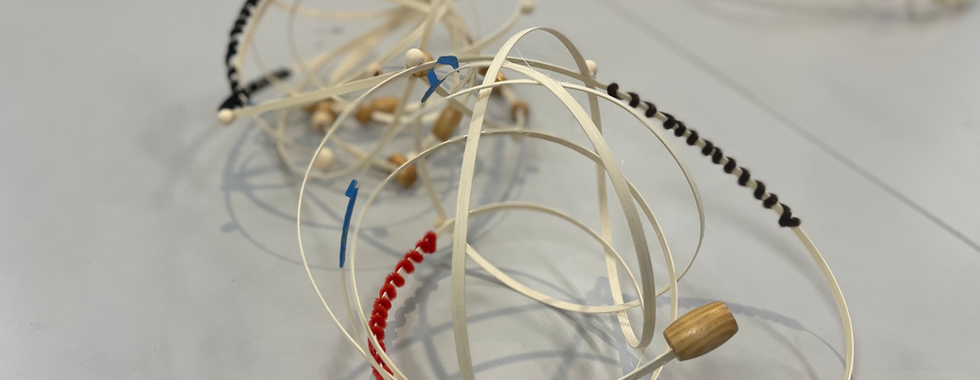

Soundscape Visualization III: Sound Sculptures

Soundscape III

Power in Numbers

Programs

Locations

Volunteers