ilayda

altuntas

Ziyu Feng

This project includes three soundscape activities: creating sound maps, maintaining sound journals, and producing soundscapes, along with visualizations of the resulting soundscapes.

Soundscape I: Child-centered learning/places

Sound Journal

I chose the San Diego Zoo as my research site because I conducted this study on a Saturday and wanted to select a place with high family engagement and opportunities for children to interact with their surroundings. The zoo provides a unique setting where children can learn more about nature, spark their curiosity, and immerse themselves in a natural experience.

I recorded sounds and observed hummingbirds in their habitat, an indoor space featuring diverse bird species and a vibrant natural landscape. The hummingbird habitat is also highly suitable for implementing place-based education in research. As Kissling and Barton (2015, p. 51) explain, “Place-based education examines and cultivates integrity in and from places. Rather than abstractly framing subject-area content, place-based educators ground their pedagogy and curriculum in the complexities of their students’ lives and surrounding communities.” Thus, the hummingbird habitat can help children fully immerse themselves in the ecological environment.

I primarily recorded the sounds of birds. The rapid wing flapping of the hummingbirds intertwined with the calls of other birds, creating a vibrant soundscape. Additionally, the soft sound of flowing water added to the ambiance. The natural sounds, combined with human voices, visitors’ footsteps, and children’s laughter, created a dynamic contrast. Inspired by this auditory environment, I envisioned “imaginative pedagogy” rooted in children’s sensory experiences and place-based education. Within this framework, teachers should encourage children to imagine themselves in different environments, perhaps in a rainforest, or envision themselves in roles such as botanists or biologists. This embodied experience can help children create a mental “imagination space” to explore the world and develop their creativity.

Through recording sounds, I aim to use sound as a tool to inspire children’s creativity. Children can imitate natural sounds to create unique artwork while developing their perception and understanding of natural ecology.

References

Kissling, M. T., & Calabrese Barton, A. M. (2015). Place-based education:(Re) integrating ecology & economy. Occasional Paper Series, 2015(33), 6.

Sound Map

Soundscape Visualization I: Printmaking

I used carved images of birds and trees to express the recorded sounds of birdsong and the natural environment I created. The birdsong is crisp as if whispering nature’s stories, full of life and vitality. The sound of the trees conveyed through the rustling of leaves in the wind and the gentle sway of branches, brings a rhythm of tranquility and harmony. These sounds intertwine to create a vivid natural scene, a layered, lively nature soundscape. Through this symbolic artistic expression, I echo the layers of sound in the recordings and attempt to visualize this auditory atmosphere, creating a space suitable for children’s learning and drawing. In this environment, children can engage with the singing of birds, the murmurs of trees, and other natural sounds, gaining inspiration and experiencing the immersive calm that the flow of sound brings to the space.

Soundscape I

San Diego Zoo. Animals not only symbolize the progression of history, but their evolutionary processes also reflect changes in human society. The sounds and behaviors of animals are not only manifestations of natural history but can also be seen as part of cultural memory and social cognition. These sounds convey information about biological evolution while also embodying traces of human-nature interaction throughout history. In this way, sound becomes an important medium for understanding history and culture, allowing the symbiotic relationship between animals and human society to be reinterpreted.

The sound elements in the soundscape include:

Hummingbird chirping - This recording was captured at the San Diego Zoo, symbolizing exploration of the place while conveying a sense of remoteness. The hummingbird's chirping evokes the vitality and freedom of nature.

Children’s laughter - This sound element originates from the design of a child-centered educational setting, forming a contrast with the hummingbird's chirping. The laughter not only embodies liveliness and innocence but also emphasizes the educational aspect of the space, creating an atmosphere full of life.

Classical music - I selected classical music as the background sound to add a soothing and harmonious touch to the soundscape. This music balances other sound elements, creating a sense of overall equilibrium and immersion.

City sounds - Two segments of urban ambient noise are contrasted with natural sounds, highlighting the clash and blend of natural sounds with mechanical noises. This contrast not only showcases the interaction between the city and nature but also reflects the tension between humanity and nature in modern life.

Sound of flipping pages - This sound symbolizes the learning function of the space, conveying the meaning of knowledge transmission and cultural accumulation.

Sound of a paintbrush on paper - I also incorporated the sound of a paintbrush moving across paper, emphasizing the importance of artistic creation in this space, representing the process of art and thought.

Soundscape II:

Sounds of the Past (Historical Places)

Sound Journal

I chose to visit the San Xavier del Bac Mission, and this is my second time visiting this historic building. I learned that “this site has been O'odham land for centuries, and the current mission site is located on the San Xavier Reservation, part of the larger Tohono O’odham Nation” (National Park Service, 2024). I sense a hint of colonialism in this place.

When I walked to the Church, my shoes made a loud scraping sound as they stepped on the sandy ground. The sound of scrap gave me a feeling of courage. Just imagine, in the 17th century, some indigenous people under the hot sun constructed this “White Dove of the Desert” (San Xavier del Bac Mission church, also called White Dove of the Desert).

As I sit in the church, some people notice me and offer a smile. However, I am the only Asian person here. I watch as people come and go. A couple of elderly individuals hold hands, sitting close to each other, whispering as they sit on the pews. One family speaks Latin—about ten people, ranging from a baby to older generations—visiting and observing the church. People of all kinds move through the space, weaving a cultural landscape.

I felt a sense of religiosity when I heard the crisp sound of a woman taking coins and the clinking as she placed them into the donation box. Reflecting on my identity as a multicultural individual, I realize that statues of religious figures, murals, and even mummified sculptures in churches are all cultural symbols of religion. However, in today’s world, these religious symbols have shifted from representing the power of religion that once controlled society to serving as cultural artifacts that teach people about historical sites.

I tried to talk with an older grandmother; she seemed very friendly. She told me that she used to come here with her husband, but now he’s gone. Although she spoke a lot, due to my limited English, I only understood parts of what she said, including how she would come here to reminisce. I also spoke with a young woman who mentioned that this was her first time visiting the church, and she came because she saw someone recommend it on Instagram. As for me, I’m here for a class activity.

Everyone has their perspective on the San Xavier del Bac Mission. I think about how the O'odham people resisted foreign invasion and how the Mission became a place of hope for them to pray for peace. I also reflect on how, in the 18th century, the Spanish rebuilt this church, bringing their art style and colonial influence. As I stand outside the church, I feel a connection across different periods. Although the protagonists of this story are no longer here, their presence is remembered.

Reference

National Park Service. (2024). Mission San Xavier del Bac. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/places/mission-san-xavier-del-bac.htm

Sound Map

Soundscape Visualization II: Digital Collage

Soundscape II

Soundscape III: Decolonial Practices

Sound Journal

When I first learned about engaging in a decolonial sound walk, I felt a deep sense of curiosity and excitement. I was eager to connect with the emotions and stories rooted in this land, hoping to gain a richer understanding of its historical and cultural significance. Visiting Picture Rock Petroglyphs intensified these feelings, as I knew I was stepping onto a site with profound ancestral importance. The sound walk was structured into three parts, each with a unique focus that guided our experience.

Soundwalking I: “Tracing the Footsteps”

In the first part, “Tracing the Footsteps,” we were encouraged to walk slowly and mindfully, focusing on the footsteps of those who have walked these lands before us. This initial stage helped me ground myself in the place and acknowledge the depth of history that surrounds us.

During the sound walk, I engaged with the land’s history through touch, specifically by feeling the texture of a leaf. I initially intended to touch the sharp spines of a nearby cactus, drawn by a sense of curiosity, yet I hesitated, feeling a mixture of caution and respect. Instead, I chose to touch a softer leaf, which allowed me to connect to the land in a gentler way. This act of touching a native plant evoked questions about the historical significance of these plants, leading me to wonder if these leaves, or plants like them, were once tended by the land’s original inhabitants—the Indigenous people.

This sensory engagement brought a new layer of awareness to my understanding of the land’s history and the Indigenous presence. By experiencing the textures and qualities of the plants firsthand, I could imagine the intimate relationship that Indigenous communities have with the land, seeing plants not merely as objects but as living, relational entities that carry stories and histories. This insight aligns with the decolonial theory of “reclaiming space” and “embodied knowledge”—acknowledging that Indigenous communities hold an inherent and embodied connection to the land, which colonialism often disrupted.

Reflecting on this experience through an art education lens, I realized how essential it is to teach students not only the historical and cultural facts but also to engage them in sensory experiences that foster empathy and understanding. Decolonial art education emphasizes the importance of moving beyond passive learning; it involves experiential, participatory approaches that encourage students to physically and emotionally connect with the subjects they study. In this sense, sensory experiences like touching, listening, and moving through the land become acts of learning and unlearning—helping to dismantle colonial narratives that treat nature as separate from human culture.

In one key moment, as I felt the leaf, I thought about its possible role in traditional Indigenous practices and daily life. This simple interaction challenged my own perspectives, urging me to view the landscape not as a passive backdrop but as an active participant in history—a history that includes colonial disruptions yet also resilience and survival.

Overall, this experience has deepened my appreciation for Indigenous histories and knowledge systems. By moving beyond visual observation and embracing a sensory approach, I gained a more nuanced understanding of the land’s layered history and the impact of colonialism on Indigenous relationships with the environment.

Soundwalking II: “Listening and Touch”

The second part, “Listening and Touch,” invited us to engage more directly with our surroundings by not only listening to the sounds around us but also feeling the textures of the environment. This session made me acutely aware of the sensory connections to the land, encouraging me to consider how touch and sound can deepen our understanding of place.

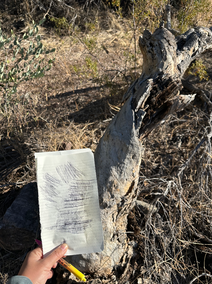

As I listened to the landscape and experimented with textures, I decided to try a simple yet evocative practice: making a rubbing of tree bark using pen and paper. This activity immediately engaged me, not just physically but also intellectually. The tree bark’s intricate texture felt like a historical document, embodying layers of time, growth, and environmental changes. This tactile experience helped me perceive the bark as a record, a natural archive that preserves the land’s history and its connection to Indigenous peoples who once engaged with it in daily life.

While making the rubbing, I became aware of the ambient sounds around me. The bird calls in the background, the subtle sounds of the bark’s rough texture, and even the faint scratching noises as I rubbed my pen over the paper brought me closer to the environment. These sounds and textures merged into an immersive experience, which evoked a sense of history—a feeling of being part of a larger narrative.

This experience resonates with the concept of “embodied history” in decolonial theory, which emphasizes understanding history not as a detached, linear timeline but as something deeply rooted in the land and sensory experiences. Engaging with the textures and sounds of nature reminded me of how colonialism has often erased Indigenous histories and relationships with the environment.

By actively listening and feeling the landscape, I was reclaiming a small part of this historical connection, acknowledging the Indigenous presence that colonial narratives have long sought to silence.

Through the sound of my pen rubbing against the tree bark, I felt a connection to those who may have inhabited and shaped this land long ago—perhaps Indigenous peoples or others who once considered this place their own. The texture and friction of the bark conveyed a kind of dynamic memory, a reminder of the labor, practices, and relationships that have woven together the cultural landscape of this place over time.

This sensory experience reflects as "embodied memory"—where materials and natural elements carry the imprints of past actions, lives, and meanings. Engaging with the tree bark in this way allowed me to access a form of historical consciousness, reminding me that the land itself retains traces of human presence, production, and cultural significance that extend beyond colonial disruptions.

The bird calls created a new emotional connection, evoking an awareness of the ever-shifting dynamics within the natural world—the changes in environment and the adaptations of living beings. Those sounds can be seen as part of an “acoustic ecology,” where the voices of nature form an integral part of the cultural landscape, reflecting both stability and transformation. This connection reminds us that each sound embodies a narrative, carrying with it historical and ecological significance that links present-day listeners to the land’s past.

Soundwalking III: “Embodying Decolonization”

The final part, “Embodying Decolonization,” focused on internalizing the experience of decolonization through our bodily presence on the land. This part was especially impactful, as it encouraged me to reflect on my own perspectives and biases, challenging me to see the landscape beyond my own framework and respect its Indigenous context.

To ensure I was fully aligned with the intentions of each session, I listened to the instructions multiple times. This careful approach allowed me to fully engage with each sound walking segment, enriching the overall experience.

During class, we each wore headphones, and I listened to the prompt instructing us to close our eyes and imagine the land. In my mind, I saw the original inhabitants of this land being driven away by invaders—a scene of displacement, escape, conflict, and war. This visualization evoked a profound sense of loss and struggle, highlighting the painful reality of displacement and its lasting impact on cultural identity and memory. Reflecting on these scenes, I began to grasp the depth of “displacement” not just as a physical relocation but as a severing of deep-rooted connections to land, traditions, and community—a form of cultural and social erasure.

From my perspective, this exercise brought to light how collective memory and identity are inextricably tied to physical spaces. The land is more than just geography; it holds layers of cultural significance and histories that are passed down through generations. Displacement, in this sense, disrupts not only individual lives but entire systems of knowledge, stewardship, and cultural continuity. The prompt’s emphasis on memory and stewardship reminded me of how Indigenous communities view land as an extension of identity and heritage, emphasizing care and reciprocity over ownership.

Sound Maps

In terms of art education, interacting with these materials provided an embodied learning experience that deepened my understanding of decolonization. Touching the stone and branches allowed me to engage with history in a tactile way, encouraging a physical awareness of the land’s layers of memory and human impact. In decolonial art education, fostering this kind of sensory connection is essential for moving beyond abstract knowledge toward a lived experience that encourages students to connect emotionally with the subject matter. By holding and reflecting on these objects, I can be guided to understand art and history as deeply interconnected with the environment, fostering respect and empathy for the land and its stories.

Moving forward, I plan to incorporate this awareness into my art and educational practices by fostering a learning environment that emphasizes multisensory engagement and cultural humility. By integrating natural elements and encouraging students to explore through touch, sound, and movement, I aim to create immersive experiences that promote a respectful connection with the environment and the histories it holds. Additionally, I intend to address topics such as cultural appropriation and cultural hegemony in my teaching, helping students understand the importance of approaching other cultures and landscapes with respect and sensitivity. This approach not only aligns with decolonial art education but also encourages students to become active participants in understanding and preserving cultural and environmental heritage.

Soundscape Visualization III: Sound Sculptures

Soundscape III

Ocean and Art Geo-aesthetics: Exploring Decolonial Practices

I have chosen La Jolla Shores Beach in San Diego as the location for Soundscape III: Decolonial Practices. The sea represents a powerful symbol of nature, fluidity, and cultural exchange. As a natural force, it embodies resilience, vastness, and a profound connection to the earth. The ocean’s currents and tides remind me of movement and drift, symbolizing both the physical journeys and the emotional experiences of displacement and migration. Throughout history, the ocean has been a conduit for cultural exchange, connecting distant lands and allowing ideas, traditions, and stories to flow between people and places. In exploring decolonial practices, the ocean offers a unique perspective that emphasizes interconnectedness, challenges boundaries, and encourages me to reconsider our relationship with nature and diverse cultures.

I have designed the following listening guidelines:

Step 1: Beachfront Meditation

Prompt: Take a moment to sit down comfortably near the water's edge. Close your eyes, and take a deep breath in, feeling the salty sea air fill your lungs. Exhale slowly, releasing any tension you’re holding. Listen to the sound of the waves as they roll in and out. Let your breathing sync with the rhythm of the ocean.

Reflective Question: As you listen to the waves, think about the journey each wave has taken to reach the shore. What feelings arise as you connect with this rhythm?

Step 2: Barefoot Walk on the Sand

Prompt: Take off your shoes and feel the sand beneath your feet. As you walk, imagine the footprints left by those who came before—the Indigenous communities who have walked these shores for thousands of years. Walk slowly, honoring the connection between your feet and the land.

Reflective Question: What do you think the ocean and shoreline mean to the original stewards of this place? How might their understanding of this land and sea differ from that of the settlers who arrived later?

Step 3: Touching the Water

Prompt: Walk to the edge of the water and let the waves touch your toes. Feel the cool water meet your skin and think about the journeys that this ocean has seen—both those of Indigenous peoples navigating these waters and of colonial ships arriving from distant lands.

Reflective Question: How does it feel to connect physically with a space that has been both a source of sustenance for Indigenous communities and a route for colonial invasion? What stories does this duality recall?

Step 4: Listening to the Sounds Around You

Prompt: Stand still and close your eyes, focusing on the sounds of the ocean and the world around you. Try to imagine how these sounds might have filled the air before the arrival of foreign ships, and how they may have changed over time. Let the sound of the waves remind you of the continuity and resilience of the Indigenous peoples connected to this ocean.

Reflective Question: What might these sounds mean to those who have long had an intimate connection with this land and sea? How might colonialism have altered this natural soundscape, and what might it mean to listen with decolonial awareness?

Step 5: Closing Reflection

Prompt: Take a final moment to stand or sit quietly by the water, reflecting on all that you’ve experienced—both sensory and reflective. Think about the role of decolonization in how we relate to natural spaces like this ocean.

Reflective Question: What responsibilities do we have to honor the original stewards of this land and sea? How can you carry this awareness forward, fostering a deeper respect and responsibility toward the environment and its layered histories?

Closing Prompt: When you feel ready, open your eyes and take one last look at the ocean. Carry this sense of connection, respect, and awareness with you as you leave. Thank you for participating in this journey and for taking the time to honor the stories and histories embedded in this place.

--

Based on the activities I designed, I began to explore the connections between sound, environment, and geo-cultural context. I reflected on how soundscapes are shaped by the natural and cultural elements of a place, each layer of sound carrying stories and histories unique to that environment. The surrounding sounds from natural elements like waves, wind, and birds to human-created noises form a complex auditory experience that speaks to the identity of the space. As a cross-cultural art educator standing on this entirely unfamiliar shoreline, I can’t help but reflect on the history of this ocean and its significance within the context of geo-aesthetics. The ocean carries unique aesthetic and social meanings across different cultures. In my Chinese cultural background, the ocean often embodies a sense of “emptiness,” a profound, inclusive space filled with room for imagination. The vastness and depth of the sea inspire awe, like the “emptiness” found in Chinese landscape paintings, which imply endless space and meaning, allowing the viewer freedom to imagine and reflect. However, for the Indigenous peoples of this land, the ocean may be more than just an object of aesthetic appreciation—it carries multiple meanings related to life, spirituality, and identity. The ocean is their resource, pathway, and bridge connecting them with their ancestors. Geo-aesthetics, in this context, is not merely an appreciation of natural beauty but a profound connection to land, culture, and history. Geo-aesthetics encompasses my sensory experiences of natural landscapes and our understanding of how these landscapes relate to our culture, identity, and social structures. For Indigenous peoples, the ocean may represent belonging, heritage, and protection, a geographically rooted relationship passed down through generations and forms a crucial part of their worldview and social structure.

Also, geo-aesthetics reflects power dynamics. For Indigenous communities, the ocean is intertwined with their daily lives and carries their knowledge systems and survival wisdom. Yet, with the arrival of colonial forces, the ocean gradually became an object for conquest and exploitation, its original cultural significance overshadowed by dominant narratives. As an outsider and observer, this reflection leads me to consider how I might approach these Indigenous perspectives with greater respect and understanding. It encourages me to bring this diversity of geo-aesthetic meanings into my art education practice, focusing not only on the natural beauty of the ocean but also on the historical memories and cultural meanings it holds.

I connect my reflections with Kraehe’s (2015) observation that “the fact that their counter-narratives emerged in fragments, rather than as comprehensive social or institutional critiques, does not lessen their significance” (p. 208). Building on this idea, I reflect on the significance of decolonial practices in art education. Decolonial art practices do not necessarily require complete, systematic critiques to have a profound impact; even fragmented expressions and small, personal reflections carry unique power. Just as the ocean’s resonance is created by countless subtle sounds blending into a profound harmony, each fragmentary counter-narrative and decolonial act accumulates, gradually challenging power structures and cultural narratives. Through these artistic practices, I hope to advance the decolonization of education in ways that may be fragmentary but are rich with meaning, providing students with multidimensional cultural perspectives and historical reflection.

References

Kraehe, A. M. (2015). Sounds of silence: Race and emergent counter-narratives of art teacher identity. Studies in Art Education, 56(3), 199-213.